- Articles

- Posted

US Sanctions: Defense or Offense? Which Regime Will be the First to “Change its Behavior”?

The US has used sanctions for decades as a low-cost way of targeting its enemies. On their face and according to the declared policy, sanctions aim to change behaviors of “bad” governments and punish the “bad” guys. The US depends greatly on its economic / financial and political position globally in making sanctions hurt the targeted entities, but what we try to demonstrate here is our belief that the US uses sanctions not as a tool of attack, but rather as a defense mechanism to against the rise of others on the world stage and to confront its own internal crises.

An article in The Atlantic, dated 3 May 2019, titled A Boom Time for US Sanctions, noted that at that time there were 7967 US-imposed sanctions in place, ranging in size of targeted entities from individuals, to businesses, to sectors, all the way to entire governments and countries. Nevertheless, according to the US Department of Treasury, Sanctions Program, there are 35 active US sanctions programs, and they are (in order of year the current program began):

As the table above shows, US sanctions can be categorized in terms of the scope of their target within four general categories:

First, sanctions that target specific entities and individuals.

Second, sanctions that target specific countries.

Third, sanctions “related” to certain countries, which means they do not only target the specific country, but also any individual, business, sector, or country that deals with the country, if Washington wishes to do so.

Fourth, sanctions under broad titles, which enables Washington, if it wishes to do so, to target any individual, business, sector, or country, anywhere in the world.

A Necessary Margin

It suffices to take a quick look at the currently active US sanctions programs shown in the table to come up with a simple and clear conclusion: to say that the sanctions target specific regimes and not countries is a complete nonsense. Has the regime in Libya not fallen? Yes, the sanctions continue. In Sudan? Yet, the sanctions continue. In Iraq? Sanctions are still there. And so on. This means that the nonsense with which US instruments among Syrians try to justify sanctions can be responded to, and even using the US Treasury data itself.

A Sanctions Bubble

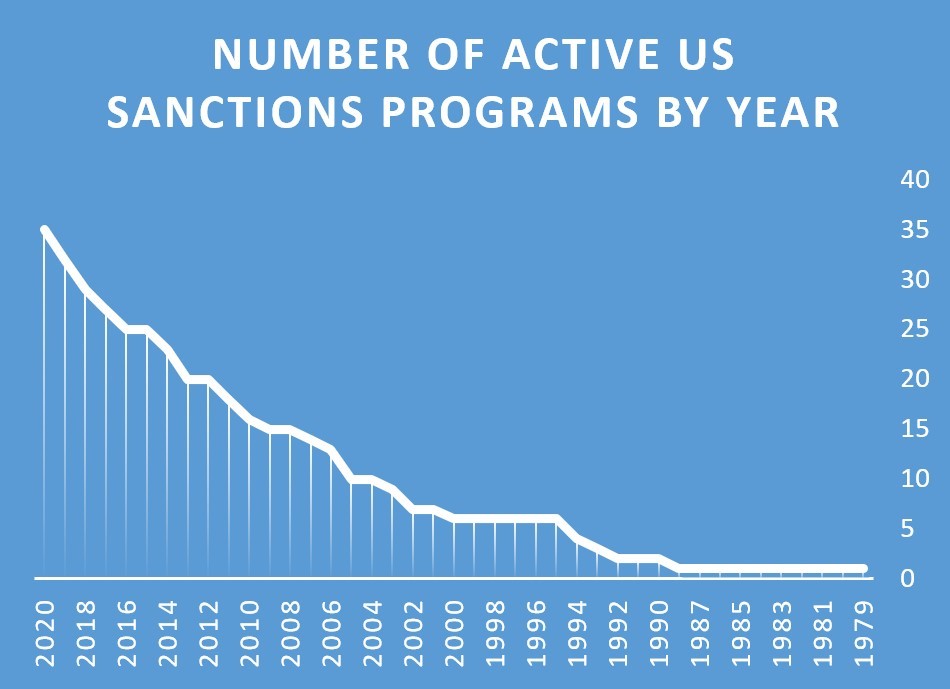

The US has imposed many sanctions programs and for a very long time, with significant explosion of their use over the last 20 years (of the 35 active programs listed above, 29 are post 2000 and 19 are post 2010). Nevertheless, for decades experts have warned about the risks of using this tool, where some have expressed concerns that “overuse of sanctions brings long-term risks both for America’s financially dominant role in the world and its leading status in international diplomacy,” according to the aforementioned The Atlantic article.

The above-referenced article also points out that the “strength of American sanctions… comes from the centrality of the United States financial system in the global economy, and in the dollar’s status as the world’s dominant reserve currency.”

The article points out two risks that would result in undermining the US’s strong global economic and political position. One risk is if financial institutions decide to run their finances through non-US channels, that is, ending the dependency on the US as a global financial center, and relatedly, dethroning the dollar. The other risk is irritating historical allies, particularly Europeans, where the impact of such irritation would not be only economic and financial, but would go beyond that to straining diplomatic and political relations.

Today, these risks are no longer theoretical. US sanctions are starting to more clearly backfire, not only are they not achieving the goals for which they are put in place, but they are having adverse effects on the US itself at all levels, especially at the economic and financial level and at the political and diplomatic level.

At the Economic and Financial Level

The US has enjoyed decades of global economic and financial control due mainly to the dollar being the main currency of trade, along with the SWIFT system. This has enabled the US to greatly influence economies all over the world, even when not directly linked, which is a major factor in using its unilateral sanctions as a tool to directly and indirectly paralyze countries’ economies.

As the US has increased its use of sanctions, countries started to look for ways to make it harder for the US to bring entire economies and trading channels to a complete stop. One way has been by countries gradually detaching themselves from the US economically, by looking for alternative economic frameworks, including the use of currencies other than dollar and other banking systems in their trading.

This has been happening increasingly at a bilateral and supra-bilateral levels, where two (or more) countries agree to use their currencies for their trade exchanges, something that China and Russia have started doing, as well as China and Turkey, for example. This de-dollarization is on the rise, not only at a bilateral level but at a multilateral level, such as the BRICS countries.

Specifically, when it comes to China, which has been one of the US’s favorite targets with sanctions, due to China’s sharp rise in the global economy, the US-imposed sanctions have not been as effective as the US has wished, and all indications point to these backfiring by having more adverse effects on the US economy than on China’s. This is becoming especially more problematic for the US in such forums as the IMF and the World Bank, where China is having an increasing leverage through its increased role in the global economy and such moves as the IMF including the Chinese Yuan in it official foreign exchange reserve database.

The US sanctions against China have counted on the idea that until now, China relies greatly on technology imports, most of which are dominated by the US, which allows the US to use sanctions to target Chinese companies in the technology sector or to take other measures such as imposing tariffs or regulations on Chinese companies listed on US stock exchanges.

Nevertheless, this is now old news. It suffices to look at the 5G technologies and the hypersonic missiles that China owns and develops, while the US has not yet reached them, in order to conclude that the US’s “technological superiority” is a thing of the past.

Furthermore, China could delist from US stock exchanges and opt for listing in other stock exchanges to ensure ability to preserve their investors. Additionally, when it comes to financial sector, China is even better off than in the technology sector as Chinese banks are well integrated into the global trading system, and are gradually decreasing their US dollar exposure, making them far less vulnerable to US sanctions.

The response to US sanctions is not limited to “hostile” countries, as with China and Russia, but has gone further to countries that are historical “allies” of the US, which are also starting to respond.

Increasingly, US sanctions are ticking off the EU and EU member states, by imposing sanctions on countries with which the EU has a lot of trade and economic relations. This has put a strain on the US-EU relations, and tensions are growing therebetween, manifestation of which we are starting to see and will likely grow if the US continues its policies in the same manner.

For example, earlier this month, the EU proposed two laws that have an effect on how companies conduct their digital business in the EU and putting limitation on how they use data. While these proposed laws target any company that conducts business online in the EU, the biggest companies would be subject to stricter rules and almost all of those are US companies like Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Apple. (Source: EU proposes sweeping new rules for online business that could force fundamental changes for digital giants, The Washington Post, 15 December 2020). While this, on its face, is not a direct response to US sanctions per se, it is definitely a response to US economic practices and policies, a major part of which are economic sanctions.

At the Political and Diplomatic Level

US policies around the world, through unilateral sanctions and other practices that aim to “destroy” anyone that challenges US “supremacy”, are also antagonizing friends and foes alike. The US, with extreme arrogance, treats all international forums and organizations as if they were its own enterprises where it has the final say. While this seemed to somewhat work since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it is no longer the case, and US bullying no longer yields the “desired” results. We saw a rise of this behavior over the last few years, which was responded to by the US by withdrawing or threatening to withdraw from international organizations like the WHO, WTO, UN Human Rights Council, and others.

It has also become more noticeable that alienation of the US on the world stage is on the rise, with historical allies, especially the West, increasingly taking positions that are not in line with the US positions in such forums like the UN Security Council, where the US is more frequently finding itself alone (or if lucky with one of the other 14 UNSC members) voting opposite of the remaining members or its proposed resolutions being overwhelmingly rejected.

In Summary

The US policies towards the rest of the world, if looked at through the sanctions lens reveal the direction in which the US is going with respect to its position globally. While on their face, policies of this type seem to be a move on the offense, in reality, it is a defense mechanism with which the US tries to slow down the rise of other economies.

Over the last decade or so, this type of behavior has started to greatly backfire, with more and more countries, whether affected directly or indirectly by US sanctions, are starting to take counter actions with gradual detachment from the US at both the economic / financial and political / diplomatic levels.

Some countries are starting to propose measures that rise to the level of sanctioning US companies, but soon enough we might start seeing blatant economic sanctions imposed on the US. What is even more significant is that the actual isolation of the US from the rest of the world is already underway and irreversible unless there are significant changes in the way the US behaves, which means ultimately a complete change in the existing system and establishment.

If the US is always boasting that the objective of its sanctions is “changing the behavior of regimes” (though reality indicates that the US is happy with the persistence of these regimes as a basic component of the chaos and instability equation), perhaps the US itself will be the first country whose behavior actually changes due to US sanctions.

Reem Issa

Reem Issa